Dear creature,

Writing to you through scattered light beams and blasts from the blue. It’s been slightly June gloom on the mountain, but much has been brewing in the mi(d)st of it all (and not only kettles and firewood).

With a summer like this I start to wonder - did we get it wrong? Is the world actually cooling after all? Shall we soon be looking back on ourselves through a bed of icicles? Because it shivers. But then I remember. I remember that we here in Ireland are blessed with a sort of micro-climate in and of itself, being not only an island but also one that looks upon eternal Atlantic. We are swamped with whatever has spent its time gathering momentum out on the waves - storm or shine. And though the weather is often a point of complaint here, on the isle, we are blessed to inhabit a relative garden at a time of global drought. To watch the world re-birth itself at every turn.. Drip drip.

So here’s to the clouds that keep us dreaming.. ( I am currently living in a barn along with a family of pine martens, falling asleep to the sound of them racing nocturnally through the walls. The joys).

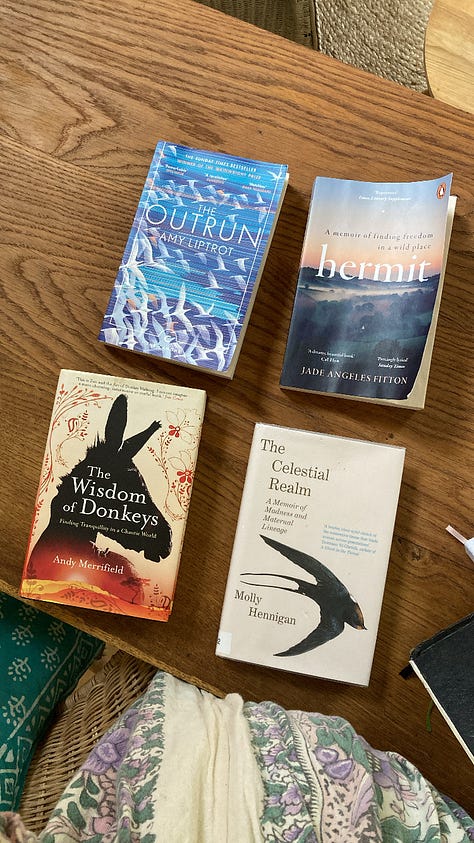

The books I am going to review below are:

The Outrun by Amy Liptrot,

Hermit by Jade Angeles Fitton

The Wisdom of Donkeys by Andrew Merrifield

The Celestial Realm by Molly Hennigan

A wise donkey, an outrun, a hermit in the celestial realm. Four books questioning and constructing the art of human-being-ness.

Review: The Outrun, by Amy Liptrot, 2015

The Outrun, 2015, is a memoir of Amy’s healing journey from alcoholism through rehab and an eventual return to her home in Orkney, after ten years living outlandishly in London. The book begins in present-day, Amy ‘washed up’ on the shore at Orkney, wondering what just happened and how she got there.

Amy left the quiet, rugged life in Orkney in a quest for a louder, freer one - but one that eventually drowns her out. Woven throughout the book are humorously poetical descriptions of the ‘wild-life’ in London, and how it so seamlessly tucks one inside of it. She aptly describes the city of London as an island unto itself - one that holds you in, what for her was a sort of destructive embrace.

I can understand the popularity of this book - her (sometimes self deprecating) humour, her simple turn of phrase that carries us in the present-moment, her openness and realness about the pains of alcoholism, and how it remains, like a current in her blood even when she no longer touches the stuff.

“I am struggling with my thoughts. It is as if there are two separate parts of myself: the one that took me to rehab and AA meetings.. and the one on the other side dreaming of a bottle of wine and that this, despite my actions, is somehow the real me”.

The description of this split of selves - the one a voice that speaks, the other that takes action, truly makes us, as readers, cheer along with her in its honesty and wit.

What struck me was her hard realisation that even though the ‘dream’ - moving away from home and discovering herself - had long turned bitter, and even though she deeply knew she was unhappy, she couldn’t give in to herself.

She writes “Sometimes I’d be walking down Bethnal Green Road, surprised by tears rolling silently down my face.

On the island I was big. It was secure and unquestioned but all I wanted was to leave.. In London it was not possible to look everyone in the face”

What struck me in her work is not only the deep appreciation and connection to nature but also a sense of togetherness that helped her heal - how the AA community offered an anchor:

“We went into detail about our pasts and I shared dark and shameful things I had never told anyone else - we all did and it created trust and a bond between us unlike anything I’d experienced before”.

When she moves back to Orkney she goes through a period of isolation and incubation (like Jade does in ‘Hermit’, which I shall review next) on the island as Papay, living in a small cottage alone. It is this time, being alone with her thoughts, that the pull to alcohol is strongest and she must demonstrate the most will against what pulses in her veins :

“People like to tell me I’m looking ‘well’ but there are late hours alone when my heart is an open wound and I wonder if the pain will ever stop brimming fresh.. At these times, drink suggests itself as a solution”.

As a reader I can feel her tension through the pages, her clamouring grip on sobriety and self. I think that is part of the brilliance and rapture of this book - the present-moment voice drags us in and we are on tenterhooks hoping she remains in recovery. Like Amy on the brink of herself - we are left on continual edge.

Overall I enjoyed this book. There’s so much to hold in it - how easily we can fool ourselves into believing we’re fine, we don’t need to have experienced severe addiction to relate to Amy’s will to thrive, her thirst for stimulation, her rush towards anything that sparkles (she’s lucky she eventually finds it in stars instead of wine bottles). It’ll make you want to step outside. Amy shows how unfathomably intoxicating everyday existence take a moment to pause and reflect.

Through mesmerising descriptions of the living landscape of Orkney - “I’ve given up drugs, don’t believe in God and love has gone wrong, so now I find my happiness and flight in the world around me” - Amy truly is “all eyes” and her gift to us as readers is a dance and a discovery.

4/5

Review: Hermit, Jade Angeles Fitton, 2023

I suppose the theme of solo woman wandering into the wilderness continues with this next book by Devon writer Jade Angeles Fitton.

Now I have a real soft mushy place in my heart for this memoir. A story of a young woman’s call to independence and autonomy after an abusive relationship, she finds herself stranded without a car, alone and quite at home in a barn in the rural wilds of Exmoor. The opening pulls us into the immediate experience of Jade’s abusive entanglement, her disintegrating sense of self and her partner’s subsequent, rather abrupt leaving her - alone, in a barn, without a car, with an emptiness so open she feels she might burst. And though she herself recognises that her joy of being alone is a reaction to a traumatic experience with a fellow human, she starts to believe that there is something more to it - thus emerges her research into hermits, and past figures in history who chose to pass their days alone. A fascinating blend of memoir, nature writing and historical reflection ensues.

“They aren’t tears of grief that are cooling.. Strangely, I do not even feel loss.”

“I am filled with a childlike excitement at the prospect of being able to enjoy this place in peace”

There is a dreamlike lilt both to Jade’s prose and figure of movement through the landscape of Britain - she seeks, more than a stable base, a sense of belonging and roundedness in the land beneath her feet. We are carried through the book, from the barn, to a rented holiday home in Devon, back to London briefly, a love affair, engagement and a move to the island of Lundy just as the pandemic hits. But never in the book do we feel we are floated - we are carried by the language, and the comfort of the wild. Her home is in herself, and its a ‘self’ she’s always meeting. There is always a kind of spiritual sense of environment:

“It’s best not to allow myself to become to connected to a place.. but my connection to the barn runs deeper than the building, the connection I am feeling is to the land surrounding it and there is plenty of that for miles around”

“With the abundance of life that comes in Spring comes an abundance of death. You see it everywhere.. gull wings with no body, looking as if they have been left for an angel to wear. The storm has created chaos, but it will also provide the materials for life to continue.”

What I found most to be the highest slant of the book, the blessing, if you like, of the author was this - sometimes, we must be alone and away from it all in order to heal ourselves. We hear so much, nowadays, about the damaging effects of isolation on health. We hear so much about togetherness and community in this era of division. And I do believe that we are stronger as one. That we must gather and recognise ourselves as perfect pieces of a mystery. But looking back there has always been splinters, loner types, mystics levitating in caves, monks living on rocks far out at sea - there has always been those seeking the soft, barren edge. But a lot of the time these historical figures did not have smartphones, no fear of missing out, no deadlines - only the gentle twitching of the forest, the company of birds. There is solace to be found away from all the noise and nonsense. There is healing to be had when we make the intention to be alone - when it is a conscious, loving choice.

As Jade writes: “The body says Only when I am far enough away will I allow these cells of mine to regenerate, only then will I give you a new life. Only when the body is safe will you sleep all night”.

At the end of the book, Jade has reemerged from her hermitage but she holds her ideals tight to her chest - of living, simply and secludedly. She finds love.

Thank you, Jade, for writing this book - through your art, my mind wandered into every pocket of a Cornish hedgerow I’d ever been and nudged me toward sleep.

5/5

The Wisdom of Donkeys, Andy Merrifield, 2008

This is the kind of book you’d gift a donkey lover gushing something like “I found just the book for you” in order to commend their adoration of these benevolent, divine creatures. It was also a personal fascination for me as I have fond memories of taking our donkey, Pippi, on a mountain pilgrimage when we were young girls.

But this book, however dated, is utterly timeless - just like the donkeys themselves - those beings whose being is time. As the poet physicist Carlo Rovelli writes “Our being is being in time - its solemn music nurtures us, opens the world to us”.

The memoir documents a journey the author takes with his neighbours donkey and is at once philosophical musing, past revisiting, and acutely present day detail.

He infuses humour with love: “I’m combing Gribouille. He’s the donkey who doodles, who scribbles freely on a page.. Gribouille equally implies someone a bit simple, maybe even a bit of an idiot, a lad after my own heart”

“We’re a travelling minstrel show, a couple of medieval troubadours hopping from one village to another, entertaining humans and animals alike”

We are led on a journey through a picturesque landscape through the mind of man into the hypothetical musings of a donkey named Gribouille. He often ponders the donkey’s thoughts and places them against his own - a sweet companionship forms.

“Gribouille stares at me, curiously.. we keep walking, hearing voices in the field, voices inside my head. The poor beast is listening, listening to my thoughts, without answering one word”.

There is kinship between them, a bridge:

“Things work differently with a donkey on a dirt trail: patience becomes a daydream that gently rocks from side to side, like a baby’s cradle, or like a sailboat out on a windless sea. It’s the gift of relish the rhythm of precise steps, of treading slower yet going farther..”. The ex New Yorker yearns only to be more donkey.

The secrets of this at superficially simple story are concealed by a donkey’s warm coat and twisting ears, bountiful description of the countryside, trees and sheep. At the core of it all is the necessity of daydreams in our lives. Daydreams like blood, like water, the ones we breathe. How necessary they are to our own survival: “I’ve felt long ago that the grown-up world isn’t all it’s cracked up to be, that I had to invent my own truths to get by, that the realm of possibility lay elsewhere..”

“our little life is rounded with reverie rather than sleep, and daydreaming - even about donkeys - no matter where you’re sitting, no matter what tempest besets you or shipwreck befalls you, never harmed anyone. Least of all yourself”.

I was besotted by this book, and warmed. It is whimsy, thoughtful, gentle and reminding. It is a sleepy read, a breeze, a slow, evenly paced trek but it is filled with insight and a sort of silence. Breath by breath, hoof by hoof. Noticing.

The Celestial Realm, Molly Hennigan, 2023

Best till last? Perhaps, maybe.

This is a beautiful, enveloping collection of personal essays. Subtle, delicate, touching. I found it sparkling on a shelf in the local library and knew it was meant to be.

Every page quivers. I was pulled, seamlessly, into the world of the author and her loved ones. Horrified at times, at the care system here in Ireland, and heartened at others.

Molly documents her relationship with her grandmother and traces a long family lineage of institutionalisation and mental illness. Her relationship with Phil is described in a very sensual, visceral manner imbued with love:

“In her intonation and lilt, when singing and also speaking, Phil stressed and rhythmically implies power and loss, mourning and epiphany, all at once. The heights and depths of ethereal meaning for her drag and surge through her vocal cords, sharing with me through sound a taste of the pain and beauty she feels.”

Molly very acutely and tenderly describes the dehumanisation that occurs when one enters a mental institution, and the complexity that arise when we speak of what it means to be ‘crazy’ or unwell, the multiplicities of truth when trauma is involved:

“I have been complicit in layering fiction over truth for her. To be a patient in a psychiatric ward is like dying. You are stripped of your autonomy while any sense of self is bleached and sterilised.. Days drag into blind repetition of habits and compliances.. You are an inmate. You know this. Your family who visit know this but they distract themselves”

“As I trace my own maternal lineage and find pockets of it warm and encouraging, I operate from a place of fearing knowing that the present-day institution is not engaging in its equivalent deep dive”

Threaded throughout the book is the cold, immaculately cardboard clean of the mental hospital, its sameness void of seasons. Her grandmother loses grip on time, seasonality - her reality is skewed. Molly shows how the institution itself plays a role to play in her grandmother’s poor mental state:

“I visit her in the winter and she says I should probably get on the road soon, it must be so late. It is only around five, late afternoon.. She has no concept of time really.. she has an institutionalised concept but not a natural one - it is punctuated and marked by meals she is brought. She has lost her feeling for Time and light and seasons.. And so we don’t talk about Spring being a turning point for that, and it being my birthday, and it being St. Brigid’s Day”

There is a poignant, beautiful moment of when Molly and her boyfriend take Phil on a day trip to the Wicklow mountains - the scene, wild and true, feels more like a fiction for Phil, who seldom sees sunlight and is years offset.

“The mountains circle the hospital but the aspect of her various bedrooms over the years certainly never demonstrated it..Tears, just from the wind, streamed back along her temples in a straight line, slipping into her ear canal that could hear nothing.. Everything was felt.. We walked four steps. The length of the car. We turned again and slowly walked back”

Molly brings to light, in this work, the importance of the wild in our collective remembering.

In contrast to the other three books, this book focuses more on human-human relationship over the natural or animal one. It is, therefore, perhaps more complex and close. There is an ever-present sense of not only Molly’s relationship to Phil but also her great grandmother, her own mother, and female family members beyond them, often through detailed description of Phil’s speech, she brings a voice back to a woman otherwise voiceless. The work is multilayered and fascinating to read:

“Each time she sings ‘Macushla’ it feels like something is being summed up.. Not love itself, but the act of loving something unloved to date. Perhaps it is arms reaching through the years, enfolding and binding me.. Something in her voice sounds like it has been there longer than she has been here singing. I don’t exactly feel closer to her as she sings, but closer, through her, to someone else”

““As I trace my own maternal lineage and find pockets of it warm and encouraging, I operate from a place of fearing knowing that the present-day institution is not engaging in its equivalent deep dive”

There is an honesty to Molly’s writing at once ‘celestial’ as the title goes but also earthbound and bodily.

It was a poetic dive into the beauty inherent in pain, the generational love that surpasses, a love stronger than mind, body, self. I flew through this book like the gorgeous swallow illustration by Denise Nestor - enchanted.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to tricklings to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.